Europe’s China debate has become a test of how far the Union can turn a broad strategic consensus into coherent action. Since 2019, Brussels has framed China as a cooperation partner, economic competitor, and systemic rival – an institutionalized hedge that seeks flexibility rather than binary alignment. Spain has internalized this logic, but in a manner that reflects its own political economy. It supports the EU’s economic-security agenda, yet avoids steps that could entrench an open-ended confrontation or expose key domestic sectors to retaliation.

This posture can be described as a “Europeanist hedge.” Madrid’s China policy is neither revisionist nor evasive; it accepts the EU’s problem diagnosis and the language of de-risking, but translates both into a strategy that privileges negotiated off-ramps, risk-managed engagement, and EU-anchored solutions over unilateral hardening. Crucially, this hedge does not deny coercion risks; it seeks to manage them in ways that are politically sustainable for a “non-frontline” member state.

Such an approach unfolds across two levels. At the EU level, Spain bargains within a framework it broadly endorses. At home, policymakers confront sectoral exposure, an industrial strategy centered on the green transition, and coalition dynamics that temper the appetite for escalation. These constraints do not produce obstructionism, but subtler forms of moderation: abstentions rather than vetoes, calibrated implementation rather than maximalist enforcement, and persistent pressure for negotiated outcomes once retaliation becomes credible.

Seen through the lens of weaponized interdependence, this behavior is intelligible. Asymmetric positions in trade, finance and technology networks give external actors leverage over specific EU member states. The central analytical question is therefore not whether Spain is “soft” or “hard” on China, but how EU economic-security policy internalizes – or fails to internalize – the distributive politics that shape such hedging behavior across the Union.

From EU Doctrine to Spanish Strategy: Doctrinal Alignment Without Maximalism

At the EU level, the 2019 “EU–China: A Strategic Outlook” classified China simultaneously as a cooperation partner, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival, and called for a flexible but united European approach. Later debates about “de-risking, not decoupling” have been presented as a calibrated extension of this framework rather than a rupture.

Spanish strategy documents broadly internalize this logic. The 2021 National Security Strategy treats the Indo-Pacific as an arena of intensifying great power competition, emphasizes risks tied to critical dependencies and hybrid threats, and situates Spain’s China posture firmly within EU and allied frameworks. China is not treated as a singular, overriding military threat; rather, it is framed as a systemic challenge that intersects with economic security, technology and multilateral governance.

In parallel, Spanish foreign policy analysis – most prominently from the Real Instituto Elcano – describes Spain’s China policy as “informal” but coherent: explicitly Europeanist, broadly loyal to EU and NATO frameworks, and characterized by a pragmatic and cautious attempt to adapt to the emerging economic-security agenda without over-securitizing the relationship.

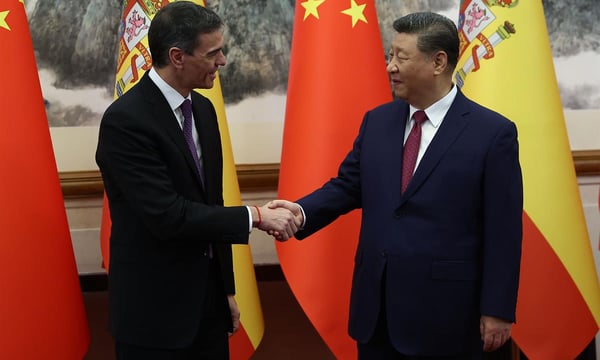

In practice, Spain operationalizes this doctrinal alignment selectively. In early December 2025, three signals in quick succession captured that logic. First, a policy piece from within the prime minister’s office acknowledged structural imbalances in Spain’s China ties while arguing for selective engagement rather than decoupling. Then the launch of the Auto 2030 Plan framed the impossibility of competing with China in EVs while advocating openness to Asian capital; meanwhile, the Commission advanced its economic-security agenda through initiatives such as RESourceEU and tighter investment screening. Taken together, the juxtaposition illustrates Spain’s Europeanist hedge: aligned in doctrine, calibrated in sectoral implementation.

The key point is that Spain’s approach is not one of equidistance between Brussels, Washington, and Beijing. Instead, it is a managed equilibrium: cooperation where feasible (climate, health, macro-stability), defensive instruments where necessary (subsidies, market access, critical technologies), and a preference for EU-anchored security tightening over unilateral national hard-lining.

Domestic Drivers: Why Spain Hedges The Way It Does

Three domestic drivers are particularly important.

First, Spain experiences China primarily as an economic and technological challenge, not as an immediate military threat in the way some frontline member states do. This shapes elite threat perception and reduces the domestic demand for overt confrontation. The National Security Strategy 2021 explicitly acknowledges China’s role in Indo-Pacific tensions and systemic rivalry, but does so within a broader catalog of global risks and opportunities. That makes an incremental de-risking logic politically easier to sustain than a full-blown securitization of the relationship.

Second, retaliation risks are not evenly distributed across the EU. Spain’s pork sector is a paradigmatic example. China’s 2024 anti-dumping probe into EU pork and by-products was widely interpreted as retaliatory signaling in the context of EU trade action on Chinese EVs, prompting immediate Spanish calls for negotiation and de-escalation. Industry figures cited at the time pointed to Spanish pork exports to China worth around 1.2 billion euros in 2023 and to Spain’s sizable share of China’s pork imports.

This distribution of exposure creates structural incentives for governments to prioritize damage limitation once coercion becomes credible: they do not need to be “pro-China” to favor a more negotiation-centered approach.

Third, the green transition is both an investment magnet and a bargaining chip. Spain’s industrial strategy centers on batteries, EVs, renewables, and hydrogen, with the explicit goal of moving up global value chains. Chinese firms are both competitors and, in selected segments, coveted partners. Public reporting on Spanish diplomacy in 2024–25 highlights announcements of Chinese investments in battery plants and green-hydrogen electrolyzers, framed domestically as evidence of Spain’s attractiveness as a green-industry hub.

In this context, Spain’s bridge-building is not merely diplomatic symbolism; it is part of an economic development strategy. Engagement is politically legible as jobs and growth, not simply as “openness.”

Trade Defense and EV Duties: Spain as a Symptom of EU Fracture

The EU’s anti-subsidy case on Chinese battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) is analytically revealing because it turned “de-risking” language into hard trade defense with clear distributive consequences.

The Commission initiated its investigation in 2023 and, after provisional measures, imposed definitive countervailing duties via Implementing Regulation (EU) 2024/2754 of October 29, 2024, while keeping the option of price undertakings on the table. The episode quickly became a test of intra-EU coalition management. In a July 2024 non-binding indicative/advisory vote, Spain reportedly supported tariffs, whereas several other large member states abstained. By the time of the binding vote on definitive duties in October 2024, Spain had shifted to abstention, joining a wider camp of member states unwilling either to endorse or to block the measure outright.

This pattern neatly captures the Europeanist hedge. Spain does not reject trade defense in principle. But once the link to potential Chinese retaliation and to Spanish sectoral exposure became salient, Madrid pushed for negotiated solutions and signaled reluctance to institutionalize a long-term escalatory trade regime.

For the EU, two implications follow. First, unity on economic-security instruments is politically contingent on whether highly exposed member states expect credible support and burden-sharing. Second, “abstention” itself becomes a meaningful signal: it is a way for governments to stay formally within the EU line while preserving bilateral flexibility – something Beijing is unlikely to overlook.

Coercion and Retaliation: The Politics Behind the Pork Probe

China’s pork probe matters because it illustrates how weaponized interdependence can operate through sector-specific pressure. Even before any duties were imposed, the mere opening of the investigation created uncertainty, mobilized domestic lobbies, and sharpened distributive conflicts inside the EU.

This is the textbook scenario for the EU’s Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), which provides a framework for responding when a third country uses trade or investment measures to coerce the Union or a member state. In practice, however, the presence of such an instrument does not eliminate the underlying collective action problem. If governments like Spain expect to bear disproportionate short-term costs, they will be structurally inclined to press for de-escalation – and to test the limits of EU solidarity – before activating coercion responses that might prolong the dispute.

In other words, coercion does not automatically harden moderates into hawks. It can equally well reinforce their incentives to seek quick, transactional settlements, especially when EU burden-sharing remains vague.

Technology and Security: Incremental 5G De-risking and a Weakest-link Union

A second fault line is critical technology, especially telecoms. The EU’s 5G toolbox and associated communications provide a framework for managing vendor and supply chain risks through national mitigation plans, without imposing a bloc-wide legal ban on specific suppliers.

Spain’s approach exemplifies incremental implementation. Royal Decree-Law 7/2022 established security requirements for 5G networks and services, spelling out obligations for operators and vendors. Subsequent acts, including Royal Decree 443/2024, have further specified procedures and oversight mechanisms. In parallel, Spanish authorities have pressured operators to reduce reliance on high-risk suppliers in core networks, and individual procurement and contract decisions have reflected a gradual narrowing of space for such vendors.

From Madrid’s perspective, this is a proportionate and cost-conscious way of translating EU guidance into national practice. From an EU vantage point, however, it underlines a structural problem: de-risking is only as robust as the least stringent national implementation. Patchwork standards create “weakest-link” dynamics in a highly integrated digital and security environment and send mixed signals to both Beijing and Washington about the reliability of EU risk-reduction efforts.

Spain’s Europeanist Hedge as an EU-level Stress Test

On its own terms, Spain’s approach is coherent. It aligns with EU doctrine, reflects domestic political economy, and rests on a plausible vision of European strategic autonomy that combines resilience with selective engagement. Yet coherence at the national level does not automatically translate into coherence for the European Union as a whole. Madrid’s Europeanist hedge reveals a structural tension at the heart of Europe’s China policy: the more uneven the distribution of exposure, the more difficult it becomes to transform shared diagnosis into collective action.

This tension becomes visible whenever the Union moves from rhetoric to enforcement. Trade defense measures highlight how sector-specific coercion quickly tests European solidarity; without credible burden-sharing, exposed governments are naturally drawn toward de-escalation, even when they support the underlying objectives. The same dynamic shapes critical technology policy. Toolbox-style governance may help identify risks, but divergent national implementation ensures that Europe’s de-risking effort remains only as robust as its most permissive member state. And in diplomacy, Spain’s instinct to act as an interlocutor is not problematic per se – indeed, it can be an asset – but it requires close coordination to avoid sending mixed signals that Beijing can exploit and other EU capitals may interpret as dilution of collective resolve.

The implication is not that Spain should simply harden its stance. Rather, the EU must make strategic coherence materially easier for member states whose domestic structures predispose them toward a moderated, risk-managed China policy. That means linking economic security instruments to tangible support for those bearing the immediate costs of retaliation, defining binding minimum standards in network-critical sectors, and embedding national outreach more systematically within EU diplomatic choreography. Only then can bridge-building strengthen rather than strain Europe’s China policy – and ensure that the Union’s ability to act does not hinge on its most exposed members.