Honduras has entered a political holding pattern unlike any since the 2017 elections, which were plagued by fraud accusations and culminated with the declaration of Juan Orlando Hernandez from the National Party as the president of Honduras. The presidential and legislative election was held on November 30, yet over two weeks later the absence of official results has left the country suspended between two competing narratives of victory and an electoral system struggling to explain its own breakdown.

What began as a routine transmission failure on election night has evolved into a prolonged test of institutional credibility. The election is plagued by contested tallies and long interruptions in the transmission results that seem to have favored the National Party candidate, Nasry Asfura. The National Party has denied the accusations, saying that it was the Libre Party – the party of current President Xiomara Castro – that tried to commit fraud all along.

This high-stakes dispute has raised questions about the external forces now circling around Central America’s most diplomatically fluid state.

The National Electoral Council has maintained that the delay stems from technical failures, but neither the public nor the opposition is convinced. Both the Libre Party and the Liberal Party, rivals in this election, have highlighted discrepancies between tally sheets collected from polling stations and the gradual updates released online. International observers who monitored the vote acknowledged the irregularities ahead of the vote and urged transparency. The United States issued a cautious statement saying that “the United States supports the integrity of the democratic process in Honduras.”

This institutional crisis is unfolding at a moment when Honduras is already reconsidering a major foreign policy decision: the country’s 2023 shift from Taipei to Beijing. Nearly two years after establishing relations with China, the grand economic expectations that accompanied the diplomatic switch have not materialized. Major infrastructure projects remain unrealized. Chinese market access proved narrower and more difficult than Honduras anticipated. Shrimp exporters, one of the country’s most important foreign-exchange earners, struggled after the Taiwanese market collapsed and China did not step up to fill its purchases, while promised investment packages remained largely aspirational. Meanwhile, China’s presence has so far been most visible in the consumer sector, through the expansion of large-scale retail chains that have made local producers drop their sales by 70 percent rather than industrial or development partnerships.

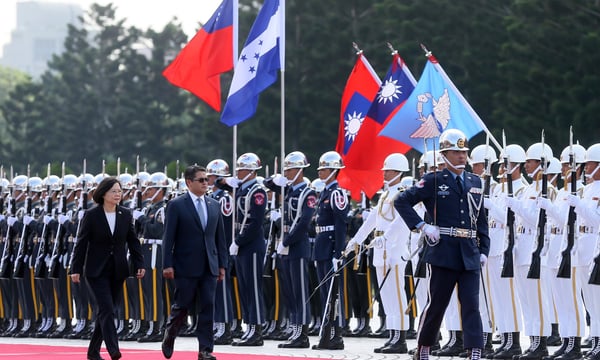

The political consequences are now visible. Both major opposition blocs, which jointly command a majority of the vote in the recent election, campaigned on restoring formal ties with Taiwan. Their stance was not framed as ideological or anti-China; it was presented as a pragmatic correction based on the observed results. For decades, Taiwan supported Honduras through agricultural cooperation, technical training, medical brigades, and scholarship programs – initiatives that directly reached local communities. In contrast, China’s engagement has been concentrated in elite channels and has struggled to produce tangible benefits for ordinary citizens.

As the vote count stalls, it will inevitably impact the geopolitical question: whether Honduras could become the first country in nearly 20 years to reverse a switch from Beijing back to Taipei. Such a shift would carry symbolic weight in a region where China has accumulated steady diplomatic wins and where Taiwan’s partners have steadily eroded. It would also reverberate beyond Central America, at a moment when multiple governments in South America and the Caribbean are reassessing the economic value of their ties with Beijing.

For China, the Honduran case is a stress test of its ability to convert diplomatic recognition into meaningful political influence. Beijing has long framed its relationships in Central America as evidence of momentum against Taiwan’s remaining allies. A reversal, especially one driven not by external pressure but by unmet expectations, would complicate that narrative and expose the limits of China’s development diplomacy.

For Taiwan, the stakes are equally high. Taipei has quietly built public goodwill in Honduras through non-political cooperation for decades. If the next Honduran government restores relations, it would represent a rare diplomatic gain at a time of mounting cross-strait pressure, and would reinforce Taiwan’s argument that its partnerships are grounded in sustained, community-level engagement rather than large but unfulfilled promises.

The United States also finds itself at a consequential moment. Washington has historically played a central role in Honduran governance, particularly in security cooperation and electoral oversight. But its influence has often been episodic, reactive, or overshadowed by domestic considerations. In the current election, U.S. President Donald Trump’s last-minute endorsement of Nasry Asfura, followed by his pardon of former President Hernandez, also of the National Party, has sparked debate about U.S. interference in Honduran politics.

The current standoff offers an opportunity for Washington to adopt a steadier, more principled posture: supporting transparent institutions while preparing to work with whichever government emerges, especially if it aims to recalibrate foreign policy away from Beijing.

Whether the electoral crisis ends quickly or drags on, its implications reach beyond the question of who becomes president. Honduras is confronting the broader question of what kind of international partnerships actually deliver results, and which foreign actors have the credibility to shape its development trajectory. The answer to that question may reshape the diplomatic landscape not only in Central America but across a hemisphere where China’s expansion once seemed inevitable.

The unresolved election has exposed deep institutional weaknesses. But it has also revived a larger debate, one that could shift the geopolitical balance of the region for years to come.