Many observers, especially in the West but also in China itself, expected political reform and relaxation to occur as China grew wealthier and more accomplished. That has not happened.

Indeed, quite the opposite has taken place. It increasingly seems that China’s developing scientific and technological abilities and achievements, along with its increased financial strength, have taken the country into a tighter, more repressive state of totalitarianism not seen since the Mao years.

Dr. Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in California, makes the case in his new book, “The Broken China Dream, How Reform Revived Totalitarianism,” that the “economic miracle” of China, and the conditions that made that miracle possible, have resulted in a return to the use of authoritarian and repressive tools from an earlier time in Communist China. Those previous years, from the inception of the People’s Republic in 1949 to the first glimmers of reform in 1978, are known for the CCP’s brutality and political incompetence, leading to the deaths and ruin of millions of Chinese citizens. Strong-man rule reigned then, with the state as the ubiquitous arbiter of every Chinese citizen’s life. Pei’s argument is that it has happened again.

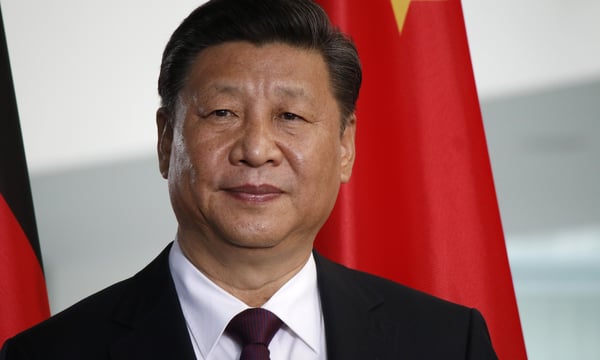

The theme of Pei’s book is in the subtitle, “How Reform Revived Totalitarianism.” In just four words, Pei precisely describes the rebirth of a modern form of authoritarianism and totalitarianism that coincides with the advent of Xi Jinping’s assumption of power in 2012.

For decades, modern China watchers, and certainly some large number of Chinese citizens themselves, hoped against hope that the economic transformation created by China’s industrial, manufacturing, and technological development would create the conditions for significant, representative political reform.

By the early 2000s, many Chinese, even CCP members, were optimistic. “We can’t go back” is a phrase that was often heard in those days when referring to the political and economic changes and advances underway in China. As Pei wrote, “Given the transformative socioeconomic changes China had experienced in the post-Mao era, such a scenario [going back] was simply unthinkable.”

But now it seems clear that the only thing needed to drag China back to the dark age of totalitarian rule was the will. And Xi provided that.

“Motives alone, however, could not explain the ease with which he [Xi] dismantled the post-Tiananmen order and reestablished a form of neo-Stalinist rule,” Pei noted. “He needed enablers – not just shrewd and ruthless henchmen, but also institutional tools – to bring back totalitarian rule.”

As Pei observed, both were “readily available” because “the fundamental institutions of totalitarianism” from previous decades had been left “largely untouched.” A “modernized and strengthened” repressive apparatus was let loose on Chinese society, and at the same time, Xi was able to launch investigations and purges within the Communist Party, neutralizing and removing threats to his position and power.

Overall, Pei’s research and conclusions put paid to the idea that the development of national wealth by definition will be accompanied by the development of a freer, more democratic society. Indeed, as Pei shows us, that wealth is just as easily used to strengthen the tools of a totalitarian society, if that is the goal of its leadership. In China’s case, for now, that appears to be the case.

The Diplomat also spoke by email exchange with Dr. Sasikumar Sundaram, senior lecturer at City St George’s, University of London, in the United Kingdom, about the totalitarian impulses evident in today’s China.

“Xi,” Sundaram wrote, “is in the midst of a difficult leadership transition period. He is aware that the time will come for him to pass the baton of leadership. And yet he is also aware of the underlying dissent and increasing number of ‘traitors,’ who are corrupt actors ready to sell out China to liberals abroad.”

Sundaram continued, “Xi’s plan from the very beginning is to cleanse the system from within and return to a disciplined long march forward. His embrace of Mao’s rhetoric is thus not accidental.” (Sundaram’s 2025 book, “Rhetorical Powers: How Rising States Shape International Order,” expands upon these themes.)

In other words, what Pei might call totalitarianism is actually just a spring cleaning, ridding the Communist Party of the corrupt, as Mao intended in his purges.

These two scholars do not differ as much in their conclusions as they do in their wording of them. Pei goes right to the heart of the matter and labels China a totalitarian state being “revived” by its own reforms. Sundaram describes a similar situation, but without using labels. In the end, the result is the same. Repression and autocracy have replaced, for now, the promise and path of greater economic and political freedoms in China that seemed so irreversible in the 2000s.

As a witness in China to most of the recent history discussed herein, I can vouch for the validity of the arc described: the deep societal repression of the 1980s, the loosening of economic restraints and the encouragement of entrepreneurship in the 1990s, the ascendancy of unbridled investment into China in the 2000s, and finally the return of the mechanisms and motives of repression in the mid-2010s to today. China has boomeranged back to its starting point of totalitarian ideology, but this time, with large though highly leveraged coffers.

That is both a statement and a warning sign of what can happen in a society that offers its people no political alternatives at all.

The Diplomat is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you purchase a book using the link above.